- Friday, 16 January 2026

- Have a HOT TIP? Call 704-276-6587 or E-mail us At LH@LincolnHerald.com

Declaration Of The Causes And Necessity Of Taking Up Arms

Written by Thomas Jefferson and John Dickinson

On July 6, 1775, the Second Continental Congress issued a pamphlet entitled "Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking up Arms", which was written by Thomas Jefferson and John Dickinson. The declaration lists American grievances but denies any intent to be independent.

The Declaration describes what colonists viewed as the effort of the British Parliament to extend its jurisdiction following the Seven Years' War which included objectionable policies such as taxation without representation, extended use of vice admiralty courts, the several Coercive Acts, and the Declaratory Act. The Declaration describes how the colonists had, for ten years, repeatedly petitioned for the redress of their grievances, only to have their pleas ignored or rejected. Even though British troops have been sent to enforce these unconstitutional acts, the Declaration insists that the colonists do not yet seek independence from the mother country. They have taken up arms "in defense of the Freedom that is our Birthright and which we ever enjoyed until the late Violation of it” and will "lay them down when hostilities shall cease on the part of the Aggressors".The opening paragraph contains the following excerpt which likens the colonies to being enslaved by the Legislature of Great Britain through violence, against its own constitution, and gives that as the reason for the colonies taking up arms:

The Legislature of Great Britain, however, stimulated by an inordinate passion for power, not only unjustifiable, but which they know to be peculiarly reprobated by the very Constitution of that Kingdom, and desperate of success in any mode of contest where regard should be had to the truth, law, or right, have at length, deserting those, attempted to effect their cruel and impolitic purpose of enslaving these Colonies by violence, and have thereby rendered it necessary for us to close with their last appeal from reason to arms.

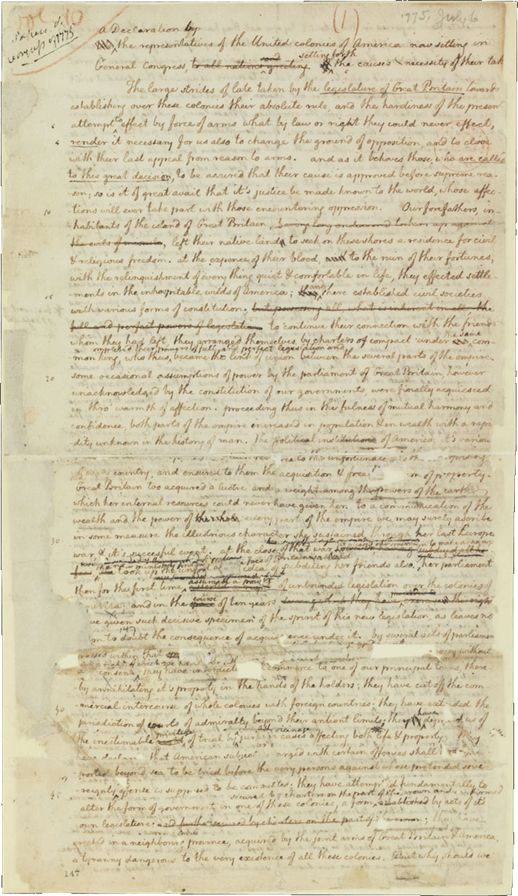

(At Right is a draft version of the text housed in the Library of Congress.)

At this point, Congress assumed that if the king could merely be made to understand what Parliament and his ministers had done, he would rectify the situation and return the colonists to their rightful place as fully equal members of the British empire. When the king sided with Parliament, however, Congress moved beyond a Declaration of Arms to a Declaration of Independence.

In the 19th century, the authorship of this document was disputed. Jefferson's version of events had been accepted by historians for many years. However, in a collection of his works first published in 1801, John Dickinson took credit for writing the Declaration which went unchallenged by Thomas Jefferson until many years later when Jefferson was nearly 80 years old. In his autobiography, Jefferson claimed that he wrote the first draft, but Dickinson objected that it was too radical. According to him, Congress allowed Dickinson to write a more moderate version and keeping only the last four-and-a-half paragraphs of Jefferson's original draft.

At least one historian stated that an initial draft was reportedly written by John Rutledge, a member of a committee of five appointed to create the Declaration. Rutledge's draft was not accepted and does not survive. Jefferson and Dickinson were then added to the committee. Jefferson was appointed to write a draft; how much he drew upon the lost Rutledge draft, if at all, is unknown. Jefferson then apparently submitted his draft to Dickinson, who suggested some changes, which Jefferson, for the most part, decided not to use. The result was that Dickinson rewrote the Declaration, keeping some passages written by Jefferson. Contrary to Jefferson's recollection in his old age, Dickinson's version was not less radical, but blunter. The bold statement near the end was written by Dickinson: "Our cause is just. Our union is perfect. Our internal resources are great, and, if necessary, foreign assistance is undoubtedly attainable." The disagreement in 1775 between Dickinson and Jefferson appears to have been primarily a matter of style rather than content.

Jennifer Baker, DAR Vesuvius Furnace

Jennifer Baker, DAR Vesuvius Furnace