- Tuesday, 17 February 2026

- Have a HOT TIP? Call 704-276-6587 or E-mail us At LH@LincolnHerald.com

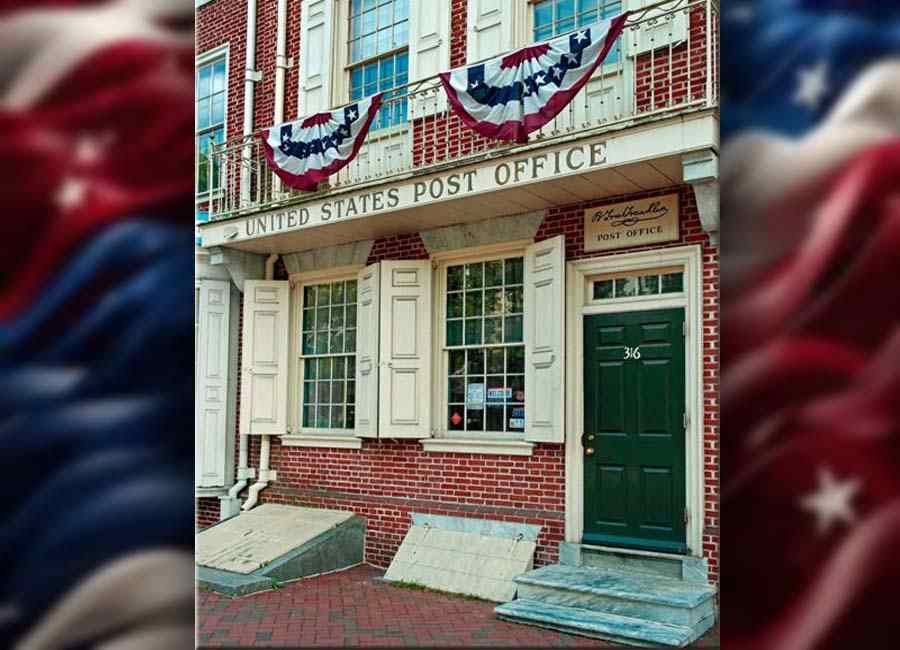

Benjamin Franklin & The United States Post Office

Our First Postmaster

In this, another in the series of articles from the SAR and DAR leading up to America's 250th birthday in 2026 we learn about our first postmaster Benjamin Franklin.

From 1753 to 1774, as Benjamin Franklin oversaw Britain’s colonial mail service and improved a primitive courier system connecting the 13 fragmented colonies into a more efficient organization that sped deliveries between Philadelphia and New York City to a mere 33 hours. Eventually, by putting mail riders out on the roads at night, Franklin managed to cut the delivery time for a letter from Philadelphia to New York and receive a reply to just 24 hours. Franklin’s travels along the post roads would inspire his revolutionary vision for how a new nation could thrive independent of Britain. But he did not even imagine the pivotal role that the post would play in creating the Republic.

Franklin also arranged for small, swift packet ships to transport mail to and from the West Indies and Canada, which complemented the transatlantic service that the British Crown provided from England and established the first home-delivery system in the colonies, according to Franklin biographer Walter Isaacson. He even set up a dead-letter office in Philadelphia to handle undeliverable mail.

Another of Franklin’s reforms—after he’d already made his own fortune—was to issue a 1758 decree that all newspapers would be transported by postal riders for the same, uniformly low rate, according to Winifred Gallagher’s book How the Post Office Created America: A History. That greatly increased the colonists’ access to information, particularly about what was going on elsewhere in the world.

As colonial postmaster, Franklin did much of his work remotely. Starting in the late 1750s, he began spending much of his time in England, where he did his job through the mail, auditing postal statements from afar and implementing his decisions by letter. The British government didn’t mind, because by 1760, the postal operation in the colonies was profitable for the first time.

By the early 1770s, Franklin’s fellow patriots had organized underground networks, the Committees of Correspondence and then the Constitutional Post, that enabled the founders to talk treason under the British radar. But Franklin’s involvement with the growing resistance to British taxation and rule eventually caused him to run afoul of British authorities.

Then on July 26th, 1775, the Second Continental Congress created what is now known as the United States Post Office in Philadelphia under Benjamin Franklin who was appointed the first postmaster general. This clearly demonstrates the level of trust American leaders had in Benjamin Franklin to have Americans’ best interests at heart. Before the Declaration of Independence was even signed, the Continental Congress turned the Constitutional Post into the Post Office of the United States, whose operations became the first—and for many citizens, the most consequential function of the new government itself.

James Madison and others saw how the post could support this fledgling democracy by informing the electorate, and in 1792 devised a Robin Hood scheme whereby high-priced postage for letters, then sent mostly by businessmen and lawyers, subsidized the delivery of cheap, uncensored newspapers. The Post Office Department was created in 1792 with the passage of the Postal Service Act. The appointment of local postmasters was a major venue for delivering patronage jobs to the party that controlled the White House.

This policy helped spark America’s lively, disputatious political culture and made it a communications superpower with remarkable speed. When Alexis de Tocqueville toured the young country, in 1831, the United States boasted twice as many post offices as Britain and five times as many as France. The astonished political philosopher wrote of hurtling through the Michigan frontier in a crude wagon simply called “the mail” and pausing at “huts” where the driver would toss down a bundle of newspapers and letters before hastening along his route. “We pursued our way at full gallop, leaving the inhabitants of the neighboring log houses to send for their share of the treasure.”

Jennifer Baker, DAR Vesuvius Furnace

Jennifer Baker, DAR Vesuvius Furnace